Spring Yang Sheng

The Dao of Longevity - Seasonal Harmonization for Spring

Dr. Henry McCann

In the Lü Shi Chun Qiu (The Spring and Autum Annals of Lü Bowei; 呂氏春秋), the classic text of Chinese philosophy from the 3rd century BCE, there is a parable that describes a strong man named Wu Huo and an ox. It says that even if Wu were to grab the ox by its tail and expend all his strength to pull the beast, he would only succeed in snapping off its tail rather than moving it backwards. Yet, a small child could take that very same ox by the ring in its nose and pull the animal forwards with hardly any strength at all. Why is this? This is because Wu Huo tried to pull the ox against its natural direction while the child pulled in the same direction the ox naturally moves. The text goes on to tell us that, for people, moving in the natural direction of life results in longevity and health. The Chinese word used to describe this ‘moving with the natural direction of things’ is shun (順), which is literally written with the characters that mean head (頁) and river (川). The image is clear – it is like diving into a river, head first, and allowing oneself to move in the direction of the water, without effort or struggle. This was the original, “go with the flow!”

Chinese medicine agrees with the idea, and a major teaching of the ancient medical classics is how humans should live in harmony with themselves, with each other, and with the natural world. The most important classic of Chinese medicine, the Huang Di Nei Jing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic 黃帝內徑; c. Han Dynasty), explains this in detail. In the very first chapter of the book the Yellow Emperor asks his physician Qi Bo to explain why even though in ancient times people were healthy and lived to at least 100 years, today they fall apart at half that age. Qi Bo’s answer is very direct – people in ancient times knew the Dao and followed the patterns of Yin and Yang (上古之人,其知道者,法於陰陽). While this statement, despite its directness, is both broad and profound, it can be understood that one of the most important methods of living a long and healthy life is to understand the basic patterns of the natural world and live in a way that moves with, rather than against, these patterns.

In modern times this seemingly simply advice seems to be harder and harder to follow. Despite the changing days, we work long hours ignoring nature’s admonition to rest sometimes and work other times. With modern shipping and refrigeration, we have access to practically every type of food there is, at any time of the year; gone are the seasonal foods of our ancestors. Certainly not all the conveniences of modern living are bad, and many contribute to our health. Yet, some very simple recommendations on how we can harmonize with the seasons are useful. In this article we will explore the current season – Spring.

Understanding the Seasons – Yin, Yang and the Five Phases

Yin-Yang Theory (Yin Yang Li Lun 陰陽理論) is one of the fundamental Chinese theories that describes the natural world and the relationships therein. The terms Yin (陰) and Yang (陽) each originally referred to the shady and sunny sides of a hill respectively, and are used to describe pairs of complementary opposites. In the body this can be seen for example as the pairs of inside and outside, front and back, organs that store or move, and blood and qi. In the natural world Yin and Yang relate to cold and hot, and the constant movement of the seasons from winter (Yin) to summer (Yang). Like the seasons, Yin and Yang also describes the course of each day as the sun sets and rises.

The second theory used extensively in Chinese medicine to describe the body, the natural world, and the relationship between the two is Five Phase Theory (Wu Xing Li Lun 五行理論). While some translators render this as “Five Elements,” this is a very, very poor translation. The Chinese word after “five” is xing (行), a word that means “go,” “travel,” or “walk.” The Five Phases therefore can also be understood as the Five Movements – in other words they describe something active and changing, not something static like an “element.” The Five Phases also are an extrapolation from Yin and Yang where two of the Phases are Yin (Metal and Water), and two are Yang (Wood and Fire), with one Phase (Earth) harmonizing and mediating between the others.

Taken together, Chinese medicine believes there is a seamless continuum between the body and the environment around us. Inside each of us there is Yin, Yang and the Five Phases, just as in the natural world there is Yin, Yang and the Five Phases. If we understand this we can see that what we do, what we eat, how we sleep, or even how we think can help harmonize our bodies with the movements of the natural world.

Spring and Wood

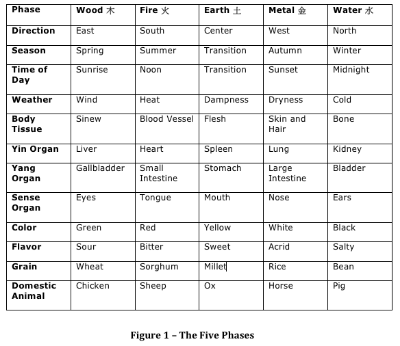

The Five Phases are Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal and Water, and each of these phases represents a wide range of phenomenon (see Figure 1). Spring is the time of the Wood phase, so in order to understand Spring we first need to understand Wood phase. In the Huang Di Nei Jing (or Neijing for short) there is a famous 8 character statement that says 春生, 夏長, 秋收, 冬藏 – “Spring gives birth, Summer grows, Autumn harvests and Winter stores.” The movement of Spring is to give birth. This Chinese character, sheng (生), also means “alive,” “unripe,” “alive,” or “cause to happen.” The image of Wood and Spring is that of a beginning. Spring is the start of grown, the beginning of plants starting to come out of hibernation. It is the time when the earth starts to warm and wake up from Winter’s slumber. As such, Spring is a time of Yang, as Yang symbolizes expansion and growth. Likewise, in our body, we should assume the movement of Yang expansion and growth in order to harmonize with the season. Thus, in the Neijing it says 春夏養陽, 秋冬養陰 – “in Spring and Summer nourish Yang, and in Autumn and Winter nourish Yin.”

The Neijing on Spring

The second chapter of the Suwen section of the Neijing is titled The Great Treatise on Regulating the Spirit with the Four Seasons (四氣調神大論). This chapter gives basic descriptions of the four seasons and how we should specifically move with them. The description of Spring starts with, “The three months of Spring, they denote breaking open the old to create the new. Heaven and earth together generate life and the Ten Thousand things begin to flourish.” Here certainly we see the basic idea previously mentioned, that Wood phase, which represents the beginning of life and the beginning of upwards and outwards movement, is associated with Spring.

This chapter continues with some basic recommendations. “Go to bed later in the evening, but rise early. Upon waking take a walk in the courtyard, loosen the hair and relax the body, thus focusing the will on life.” Since the Wood phase is Yang and represents the beginning of movement, this recommendation is understandable. While in Winter we should sleep more, in Spring we should be more active. Thus, getting up early is a good recommendation, especially with the lengthening days. Walking in the courtyard represents the admonition to do more exercise. Since the Wood phase relates to sinews (i.e., tendons and connective tissue), gentle exercises that relax and stretch the body such as yoga or Daoyin are appropriate. As the weather warms take more frequent walks outside, preferably in natural surroundings like parks and gardens.

The next section of the Nejing passage says something a bit more esoteric: “Give life and do not kill. Give and do not take. Reward and do not punish.” What does this mean? The Wood phase represents the beginning of life. Killing, taking and punishing all go against the movement of birth, creativity and freedom. So, in order to harmonize with Spring, even our thought patterns need to be adjusted. Spring is the time to start new projects, or to encourage other people’s new endeavors. It is the time to think new ideas and make new plans in all aspects of our lives. According to the Neijing, when we accomplish all of this, we are acting in resonance with the Qi of Springtime, and thus we have accomplished a Nourishing of Life. If we do not follow these seasonal recommendations we potentially harm the Liver, the Wood organ, and then suffer cold type diseases in the Summer that follows.

Eating for Spring

In Spring diet should primarily be focused on supporting normal Liver function, as the Liver relates to Wood from a Chinese medical perspective. The Liver in Chinese medicine is responsible for normal coursing and moving of the qi and blood internally. Foods that have this Yang function of coursing the qi and blood, or creating movement in general, have an acrid, or mildly spicy flavor. Acrid culinary herbs include onions, scallions, garlic, cilantro, ginger, basil, dill, fennel, and bay leaf. Additionally, Spring is the time to eat plants that are young and thus have the quality of growth associated with Wood. These include young greens, sprouts, or sprouted grains. The specific grain of the Wood phase is wheat, which is also eaten in Spring provided the person eating it has no specific allergies or sensitivities. Seasonal foods that are harvested in Spring include chard, arugula, new potatoes, asparagus, and eggs.

In general Spring is the time to eat lighter foods than those consumed in the colder weather. It is also the time to eat less. People who are relatively healthy can practice a short 24-hour fast once a week to let the digestive system rest a bit. This type of intermittent fasting still allows for food each day; for example a 24-hour fast would be eating breakfast one day, then not eating any calories until breakfast the day following (i.e., not eating any calories for exactly 24 hours). During the fast day people should consume plenty of water or light tea to stay well hydrated.

Even the method of cooking food should be adjusted to the season. In Spring foods should be cooked quickly over high heat. This type of rapid cooking leaves food, especially vegetables, not completely cooked. An example of this type of cooking is sautéing with a small amount of cooking oil. Other appropriate methods of cooking vegetable include light steaming or blanching.

One basic tea that supports Liver is the combination of peppermint and lemon. For this tea steep either bags of dried peppermint tea or, if available, crush fresh peppermint leaves in boiling hot water. Add to this liquid several thin slices of fresh lemon including the peel. Some sweetener such as honey can be added to taste. This simple tea combines the acrid flavor of peppermint with the sour citrusy lemon, a basic combination that courses and soothes Liver qi. Practitioners of Chinese medicine can use this tea as a dietary substitute for the famous Liver coursing formula, Xiao Yao San (逍遙散), which also utilizes the combination of acrid and sour flavors.

Acupressure

Qi and blood constantly circulate through the body along the Channels, the pathways that acupuncturists stimulate with needles. While needles are excellent tools for balancing the channel system, they are invasive and cannot be performed at home by the general public. However, fingers can be used as needle substitutes for acupressure.

In Spring acupressure can be done to ensure smooth movement of Liver qi. One basic point combination for this is known in Chinese as the “Four Gates” (Si Guan 四關). The Four Gates are comprised of two acupuncture points, one on the hand and one on the foot. Since the points are stimulated on both the left and the right, there are four locations in total, making up the Four Gates.

The first of the points is located on the back of the hand between the thumb and first finger. In Chinese this point is called He Gu (合谷穴) and it is found along the Large Intestine channel (Large Intestine 4; see Figure 2). He Gu is a major acupuncture point for moving qi in the body, especially in the upper part. It also stimulates the Yang qi as well as expels Wind from the body, the pathogen of Spring. It can be stimulated to treat seasonal allergies, headache, spasms in the body, and even pain in the abdomen or lower back.

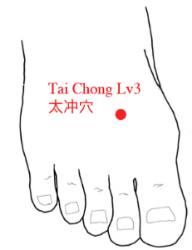

The second point of the Four Gates is Tai Chong (太冲穴), the third point of the Liver Channel (see Figure 3). This point also has a strong function in moving the qi in the body to regulate the Liver. It is found on the top of the foot in the space between the first and second metatarsal bones. Like He Gu, Tai Chong treats headaches and various pains and spasms in the body. Furthermore, Tai Chong has a beneficial effect on the eyes, treats dizziness, and seasonal allergies. It also treats painful menstrual cycles. Together, He Gu and Tai Chong are one of the most important acupuncture point combinations for ensuring smooth moving qi in the body. These points can be stimulated several times a day. To do so, apply deep pressure to the points with the thumb, until a slight soreness or numbing sensation is felt. Hold pressure for 20 to 30 seconds, relax, and then repeat several times.

Patting the Body

Patting or beating at acupuncture points or along the channels is a method of health preservation that is important in both Chinese medicine and Qigong circles. This is known as Pai Da (拍打) in Chinese, and I first learned this method from my Qigong teachers. For Pai Da, the practitioner uses a loose fist or an open hand to beat or pat at specific acupuncture points, or to stimulate along an acupuncture channel. The intensity of the patting should be strong and deep, and not just lightly at the surface. That said it is important not to beat so hard as to create pain. At the beginning the technique should start gently which is known as Wen Pai (文拍; Scholar Patting), and then progress to stronger stimulation known as Wu Pai (武拍; Military Patting).

Pai Da is slightly different from acupressure in how it works. The act of patting or beating at acupuncture points stimulates the body to send Yang qi to the surface. We can see this clearly in that the area being stimulated feels warm and can look red when finished – these are all signs of heat and Yang moving to the surface. Since Spring is the time of moving qi to the surface and the time where Yang qi is growing, Pai Da is especially appropriate then.

In Spring Pai Da can be performed along, or on points located on the Gallbladder channel. This channel is the Yang pair of the Liver channel, and as such it is also associated with the Wood Phase and Spring. Stimulating the Gallbladder channel helps move qi and blood in the Liver channel, and therefore the whole body as well. For Spring Pai Da, start patting the shoulders at Jian Jing (肩井穴), Gallbladder 21 (see Figure 4). This point is located on the top of the shoulder on the upper trapezius muscle. Use a loose fist or open hand to reach across the body, patting deeply at this point. Then, repeat on the other side of the body.

After patting the shoulders continuously for several minutes, move to the lower part of the Gallbladder channel. For this segment, start patting with a loose fist at the side of the buttocks at Huan Tiao (環跳穴), Gallbladder 30. Since this is an area of deep muscle it tolerates deeper beating. Continue patting down the side of the leg in a line, passing over the acupuncture point Feng Shi (風市穴), Gallbladder 31, and going down to finish just above the knee (see Figure 5). Repeat patting down this line several times.

Patting these areas of the body should be done for a total of about 10 to 15 minutes minimum per day to get maximum benefits. Pai Da should not be done over areas of wounds or fractures, pregnant women, or by patients with cancer. In general it is best to do Pai Da under the supervision of a doctor of Chinese medicine or an experienced Qigong teacher.

Conclusion

Many of us are so consumed with the fast pace of modern life we rarely are sensitive to the changes going on around us all the time. The wisdom of Chinese medicine though is clear. When we situate ourselves inline with the changing seasons we mimic the very flux of Yin and Yang in the universe. Moving in this flow enhances health and happiness.

While the recommendations in this article are general and can be applied by those in good health, some recommendations may vary based on the specific predispositions or disease conditions in each person. People with preexisting diseases should seek the guidance of a professional licensed practitioner of Chinese medicine who can make an individual assessment.

Happy Spring and good health!

References:

Knoblock J, Riegel J, trans. The Annals of Lü Bowei. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

Lu HC, ed. 黄帝内經(素問,靈樞)難經原文(段落難号)[The Original Chinese Texts of the Huang Di Nei Jing (Su Wen, Ling Shu) and Nan Jing]. Vancouver, Canada: International College of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Lu HC, trans. A Complete Translation Of The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine And The Difficult Classic. Vancouver, Canada: International College of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Pitchford P. Healing with Whole Foods. North Atlantic Books, 2002.

Sun LB, Wang T. 黄帝内经二十四节气饮食法 [Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic Dietary Therapy for the 24 Seasonal Nodes]. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press, 2010.

Unschuld P, Tessenow H. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen: An Annotated Translation of Huang Di's Inner Classic - Basic Questions. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Wang Y, Sheir W, Ono M. Ancient Wisdom, Modern Kitchen. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2010.

Xiao HC. 拍打拉筋自愈法手册 [Pai Da and Tendon Stretching Home Therapy Manual]. Yi Xing Tian Xia Publishing.